It’s the time of year where society’s noteworthy and notables appear on college campuses to congratulate and inspire the newest members of the college-educated workforce. While personal anecdotes extolling the virtues of a life well lived are always appreciated, perhaps what is really needed this year is frank advice on overcoming indebtedness.

Six months from now, the most indebted college graduating class in history will begin making and/or missing payments on their student loans. In another six months, a new record for debt-burdened alumni will be set and the cycle will repeat again.

Over the past five years, the level of student debt has almost doubled from approximately $600 billion in 2008 to over $1.1 trillion today. Student debt now exceeds all forms of other consumer debt, save for home mortgages ($9T outstanding). While aggregate measures of consumer debt have recovered to pre-crisis levels, this growth has been driven by the secular increase in student debt.

Other forms of debt, such as auto loans and credit card balances, still remain well below their pre-2008 highs . More troubling, while the delinquency rates of credit card, mortgage, auto loans, and revolving credit have shown continued year-over-year improvement since the financial crisis, student loan credit performance has deteriorated.

The looming student loan debt crisis has been a very popular topic in the press recently. Many have highlighted the substantial personal challenge this debt burden poses to a generation of 20-somethings who are largely underemployed and now, over-indebted . Even worse, this debt is not dischargeable in bankruptcy court, which some have argued harkens to colonial-era indentured servitude. “Bubble” concerns have also been voiced recently, driven by fear that the large growth in credit to an underemployed demographic with arguably limited short-term prospects portends some form of future financial crisis (remember subprime anyone?).

So what exactly is driving this secular growth in student loan balances? Is this indeed a classic credit binge with misspent borrowings, or rather an investment in future productivity growth? What exactly is the credit quality of this debt, and what are the implications for the financial of significant student loan default? Ultimately what effect will this phenomenon have on our economy and financial markets?

More students, ever higher tuition, lower incomes, and accessible credit leads to higher loan balances

Part of the reason students are borrowing more today than ever before is simply because tuition costs have risen at an astonishing pace. According to a recent Bloomberg article , tuition expenses have risen some 538% since 1985. To put this in perspective, that is roughly double the gain in price of medical care, which jumped only 286%, and it dwarfs gains in the CPI inflation rate which increased a mere 121% during the same period.

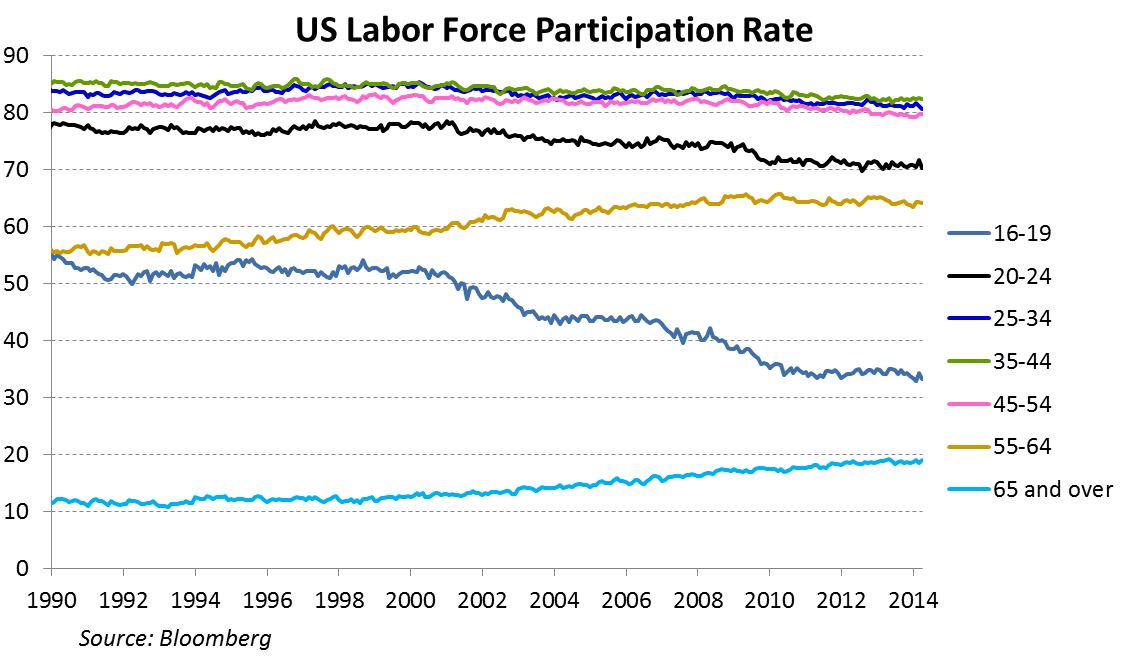

Tuition increases do not fully explain the rise in debt, however. Students have not only paid more, a larger proportion of students have financed a portion of the cost. According to a December 2013 report from MeasureOne, the percentage of students using student loans increased from 34% in 2004, to over 42% by 2012 . One of the key drivers has been the weakness in the labor markets over this periodwhich has disproportionately hurt younger workers. The labor force participation rate for college-age students plummeted following the financial crisis and has yet to recover.

Students are not able to earn as much income either during college or prior to entering college, which may have offset the need for some of their borrowing. Furthermore, given the lack of job opportunities available for this age group, many are choosing to attend college rather than enter the workforce, thus increasing college enrollment and the need for borrowing. Finally, college graduates are finding it hard to find gainful employment. Lower post-graduate incomes means lower repayment rates, which in turn means higher aggregate loan balances.

One could argue that, given the poor employment prospects, enrolling in college to improve ones’ skills is exactly the right path for young people. This makes sense as long as the skills gained lead to higher productivity/employment upon graduation and, for a large number of students, this is certainly true. Disturbingly though, there are indications that this will not be the case for a good portion of college grads. Job growth projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics report that only around 27% of new jobs created over the next ten years will require a degree. Additionally many graduates today are taking jobs that do not require a degree. For example, currently more than one million college grads work in retail. This seems to suggest that some of this increased ‘investment’ in tuition costs may not pay off, at least in the short run.

Another critical factor is the availability of loans. Student loans balances are growing because there is a lender willing to lend the capital. While growth in private loans has been stagnant, the growth in Federal loan programs has expanded tremendously since the crisis. Interest rates have remained fairly low as well. This availability of cheap credit has helped to fuel the growth in loan balances.

So is this the next bubble about to burst?

The overhang of student loan balances is expected to have a meaningful impact on the economy for some time. The magnitude of the effect is still unclear, but it will likely have both direct and indirect effects.

First, there is the risk of some sort of new credit crisis should a large proportion of these loans become delinquent. The size of these loans, at over $1T, is certainly large enough to do some damage if things go poorly. While the credit quality of private student loans has been improving, with delinquencies peaking around 8% after the crisis now falling to less than 4%, private loans remain a small portion of the overall market. Private loan underwriting follows strict credit quality guidelines, in which lending is only extended to certified schools, most require co-signers, and market interest rates are charged.

In fact, some hedge funds have recently profited from buying bonds backed by pools of private student loans that were originated around the time of the financial crisis. These bonds had sold off on fears that the credit quality would show significant deterioration due to the high levels of unemployment. However, as these pools have seasoned, the credit performance has exceeded market expectations and led to profits for bond holders.

Federal student loans, on the other hand, are extended under a needs-based underwriting regime which does not require cosigners, school certifications or an analysis of credit risk. Unfortunately it’s the federal student loan growth that has been exploding, with $1.04T in government loans outstanding as of Q3 2013, comprising the vast majority of the $1.1T student loan market. Somewhat unsurprisingly, the credit trends in federal loans aren’t nearly as encouraging. Delinquencies have risen from 18% in 2009 to near 21% today. Looking forward, it’s unclear this trend will improve as unemployment of college grads remains high and incomes of the employed graduates remain low.

Credit crises usually involve a large number of overleveraged buyers overpaying for deteriorating assets. Most often these credit crises end with a transfer of debt load from consumers/companies/banks who incurred the debt to government balance sheets. In the case of the student loans, private loan markets appear to be well functioning in underwriting credit risk and are not oversized.

Federal loans are conveniently already owned by the federal government, which can currently borrow for 30 years at less than 3% interest. While $1T in loans today is larger than many financial bond markets, it is probably a manageable debt load in the context of the federal government’s $3.7 trillion annual budget. Thus it seems as though the immediate risk for some sort of large scale credit meltdown in financial markets as a result of student loans remains low.

The indirect effects of this debt overhand seem more likely to have an adverse impact on the economy and financial markets. New home buyers are an important segment of the home market. In recent years, household formation rates have declined, with more adult children living with their parents.

As incomes for college graduates are down at the same time that the debt burden from student loans has gone up, it’s not rocket science to intuit that there will be that much less room in young adult budgets for mortgage payments. Complicating this further is the fact that mortgage underwriting standards have increased dramatically since before the crisis, and young people with little credit history are likely to bear the brunt of this. While this may not lead to a decline in home prices, it may be a headwind for further home price appreciation.

There are also likely to be social and political elements that come into play. Already the government has begun to address part of this issue through instituting low interest rates, interest rate forbearance, and exploring forms of principal forgiveness as well . Should credit losses in student loans become a large cost to society, there will likely be political battles fought between the debtors (younger post-college grads) and non-debtors with other spending priorities (older generations).

Still, perhaps the most pernicious effects of this debt burden are likely to be social in nature and hard to measure. Some of the greatest innovations in technology have come from seemingly reckless, risky ventures led by the young. The fundamental issue to overcome in this case is that creditors generally have little tolerance for failures, and the changes to bankruptcy laws in 2005 have made failure to make student loan payments legally intolerable.

While the many lofty graduation speeches being delivered this month will try to once again inspire the creative entrepreneurial impulse that has driven American economic ingenuity, this year’s graduating class, saddled with student loan debt, seems instead to be more likely to follow a “play it safe” strategy with their careers.

Article from Forbes.com